Geniuses, myths and deception

An end-of-year plug for someone else's book

Sketchwriting is over for the year, I hope. Possibly too late to be useful for Christmas, here is a long book recommendation. It’s for a friend’s book, which got me thinking about the last book I wrote, and if you’re interested in the thinks that I was thinking, here they are.

Helen Lewis’s The Genius Myth is a history of the idea that every now and then there walks among us a man (or woman, but really, let’s face it, man) who has been touched by the gods and gifted with special brilliance: a Leonardo, a Shakespeare, an Einstein. It’s a very enjoyable tour of some fairly unpleasant people, some of whom were special at moments, and some who weren’t even that, and how the idea of what a “genius” is changes with the culture.

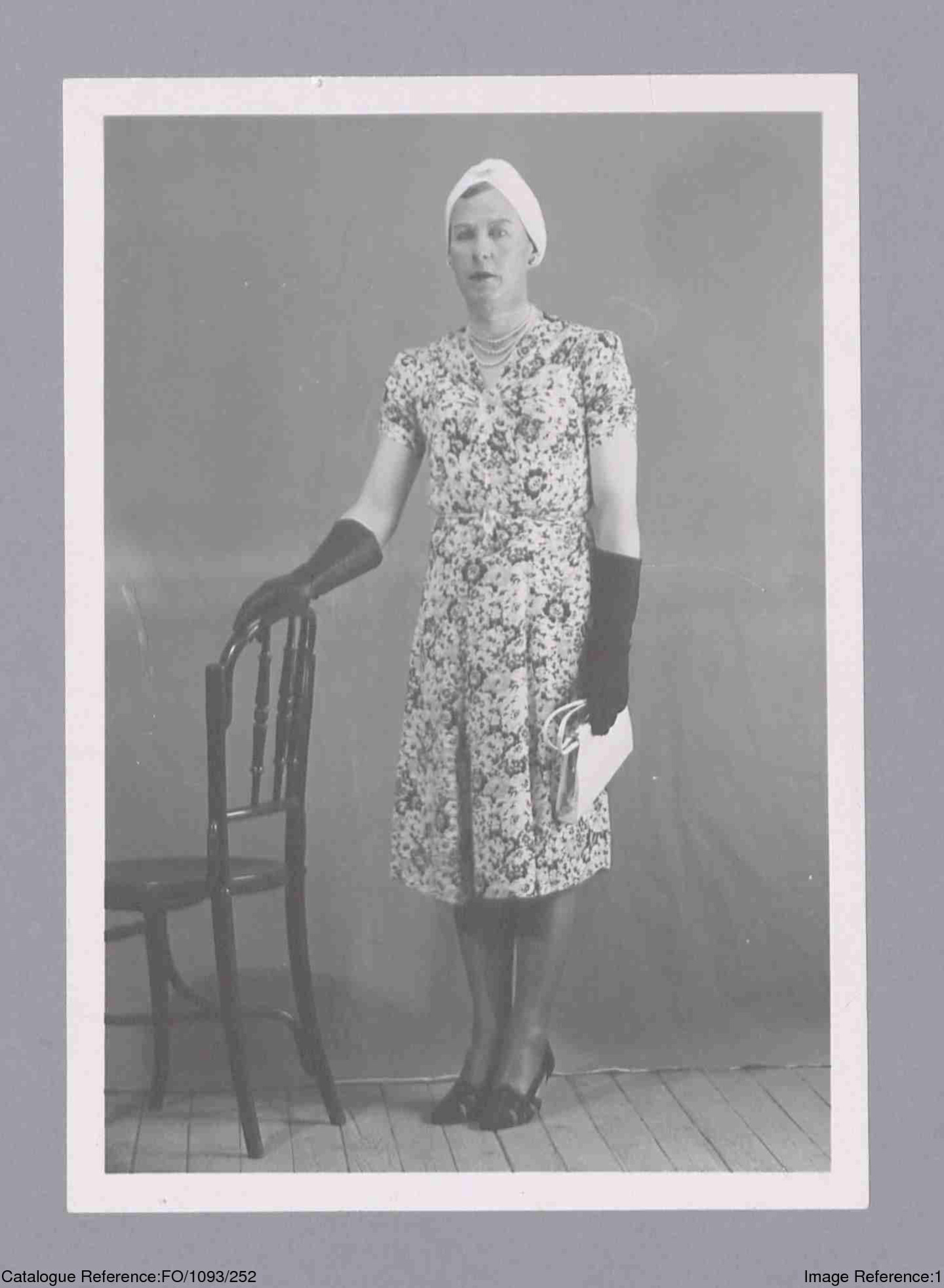

My own book, The Illusionist, is about a man who could make strong claims to genius. Dudley Clarke is not well-known, although the increasingly unrecognisable portrayal of him in SAS Rogue Heroes has probably helped a little. But his wartime innovations are impressive: in 1940 he founded the Commandos, setting out how a small unit of independent-minded soldiers could operate behind enemy lines — a novel idea in the British army of the time. His ideas contributed to the formation of the SAS and the US Army Rangers, and his legacy is in modern special forces units.

Much more than that, starting in 1941 he founded an Allied deception operation that would grow from one man working out of a converted bathroom in Cairo into a global force. The deceptions around D-Day are now fairly well-known, but they’re rarely seen in their full context: it was Clarke who had realised that in a global war, it might be possible to persuade your enemy to place troops not just in the wrong part of the line, but in the wrong country, and indeed that it might be possible to make him keep them there by creating entire imaginary armies that needed to be defended against.

Special forces would have happened without Clarke — the idea was floating out there in various forms in 1940 — but one of the questions I ask in the book is how history would have been different if, as nearly happened, Clarke had been captured by the enemy or dismissed by his own side in 1941 (whether or not it subscribed to the idea of his genius, the British Army took a surprisingly understanding attitude to a cross-dressing episode that landed him in a Spanish jail).

My conclusion is that it’s very hard to see Allied deception reaching the heights it did without him. This is partly because he really does seem to have been the only person with a full vision of what deception could achieve. Even when he explained the concept, generals struggled to get their heads around it. (One American officer, told about the plan to get the Germans to concentrate their forces in the Pas-de-Calais, replied, baffled: “But we’re not going to land in the Pas-de-Calais.”)

But listening to Helen’s book I felt chastened by her warning against falling into the trap of “genius studies”. A tale of one man whose brilliance changed the course of the war is incredibly appealing, but of course it’s misleading.

Clarke’s success was partly the result of happy chances. There was a war that presented him with challenges he could meet, at the right moment in his career: he was by this point on friendly terms with most of the senior general staff, so he could get his ideas heard. He was operating at a time when the Army kept losing, which meant commanders were keen to hear ideas that might change this.

Most particularly, I’m grateful to Helen for introducing me to the concept of “scenius”, a word invented by Brian Eno to describe the way that there is sometimes an environment that encourages creativity from lots of people. It’s an excellent way of thinking about one of the key moments in The Illusionist: at the end of 1940, Clarke was sent to Cairo.

The environment of Egypt in the early years of the war was perfect for a creative military thinker: unlike in Britain, the army was actually fighting someone. That regular contact with the enemy allowed experimentation with new ideas. Officers were far enough away from high command in London to be able to try things out. The commanders in Cairo, first Wavell and then Auchinleck and Alexander, were themselves creative thinkers, open to novel ideas and experiments. The desert was obviously different from Europe, so it wasn’t controversial to suggest you might need different ways to fight.

And Clarke had around him a diverse (by the standards of the 1940s) crew of useful people, including the writers Evan John and Peter Fleming (brother of the now more famous Ian), the soldier David Stirling, who saw a way to take the Commando idea forward in the SAS, and the exceptional RJ Maunsell, who ran counterintelligence in the Middle East with ruthless effectiveness. The team also included artists, a film-maker and a magician. After the war, Clarke’s people would become stockbrokers, intelligence analysts, corporate executives and even a vicar.

Helen’s conclusion is that “genius” is a word better applied to works or ideas than people. Clarke’s idea of a vast global deception carried out against the enemy was genius. The man himself was, like the rest of us, sometimes brilliant and sometimes daft.

Merry Christmas, one and all.

Thanks for the sketches Robert and have a good festive break.

I've got 2 audible credits, so if they're available, I'm going to get these 2 books because your sketches have helped me get through the year. Thank you